Grace Hopper built the first compiler in 1952. They said “you can’t make them understand English-like instructions.” She had a running compiler and nobody would touch it. Sound familiar? Grace had some thoughts about this kind of thinking. She had a lot of thoughts, actually.

Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper -- mathematician, Navy officer, and the person who proved everyone wrong about compilers.

A Quick History Lesson

In 1952, Grace Hopper created the A-0 System – the first compiler. The idea was straightforward: let humans write instructions in something closer to English, and let the machine translate that into the binary it actually executes. Logical, right?

The reaction from the computing establishment was… not enthusiasm.

“I had a running compiler and nobody would touch it. They told me computers could only do arithmetic.” – Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, as quoted in Grace Hopper: Navy Admiral and Computer Pioneer by Charlene W. Billings (1989), p. 74

Let that sink in. She had working software that proved the concept, and the response was “nah, that’s not how we do things.” The objection wasn’t technical. It was psychological. People had mastered assembly language and machine code. That was “real programming.” A compiler was cheating. It was a crutch. It would produce inferior output. The machine would never be as good as a human at writing machine code.

Every single one of those objections turned out to be wrong. Compilers won. COBOL happened. Fortran happened. Eventually C, Java, Python, Go – every language you’ve ever used exists because Grace Hopper was right and the naysayers were wrong.

The compiler didn’t replace programmers. It made them wildly more productive. It freed them to think about problems instead of opcodes.

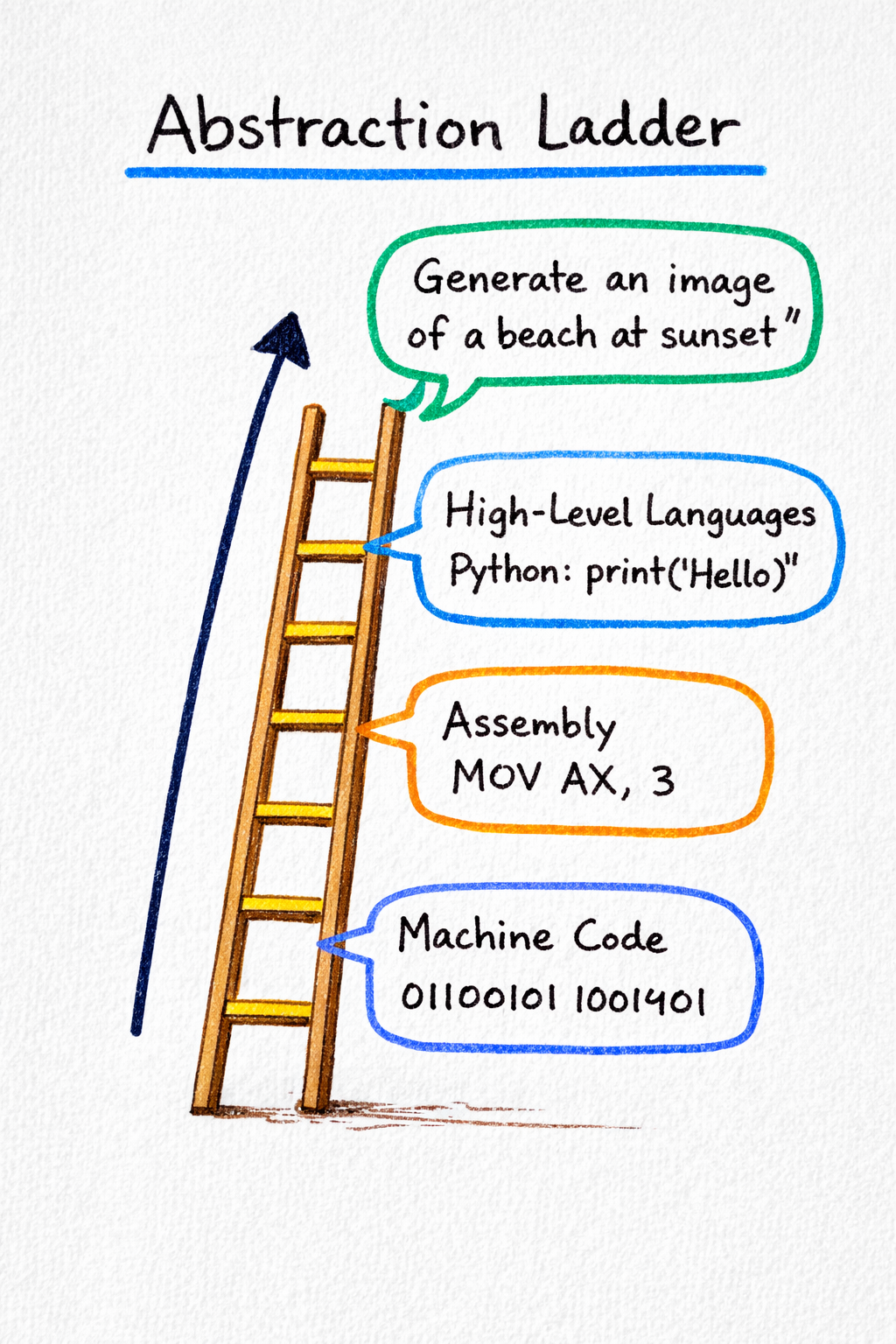

The Abstraction Ladder

Here’s the thing that keeps rattling around in my head. Look at the history of programming as a series of abstraction layers:

Machine code –> Assembly –> High-level languages –> ???

Every single step up that ladder was resisted by the people who had mastered the layer below. Assembly programmers thought compilers were toys. C programmers thought garbage-collected languages were for amateurs. Desktop developers thought the web was a fad.

And now? That next rung on the ladder is natural language. LLMs and coding agents are, functionally, a new kind of compiler. The input is human intent expressed in English. The output is working code. The abstraction is the same pattern we’ve seen for 70 years, just one more step up.

The objections today are identical to the objections in 1952:

-

1952: “That’s not real programming.”

-

2025: “That’s not real programming.”

-

1952: “You need to understand the machine.”

-

2025: “You need to understand the code.”

-

1952: “Compiler output is inefficient garbage.”

-

2025: “AI-generated code is buggy garbage.”

Same song, different decade.

The abstraction ladder. Every rung was resisted. Every rung won.

You Don’t Run Against Logic

“Developing a compiler was a logical move; but in matters like this, you don’t run against logic – you run against people who can’t change their minds.” – Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, The OCLC Newsletter, No. 167 (March/April 1987)

This is the quote that hits hardest for me. The resistance to AI-assisted coding is not a technical argument. Not really. It’s an identity argument. People who have spent years – decades – mastering the craft of writing code by hand feel threatened by a tool that changes what “mastery” looks like.

I get it. I really do. I’ve been writing code since I was a kid on a TRS-80 with 4K of RAM. I’ve invested a LOT of my life in learning how to write good software. But here’s the distinction that matters:

“I am a person who writes code” is not the same as “I am a person who builds software.”

Compilers didn’t eliminate the need to think. They eliminated the need to think about the wrong things. Nobody mourns the loss of hand-coding branch offsets in hex. LLM coding agents are doing the same thing one layer up. They don’t eliminate the need to think. They eliminate the need to type boilerplate, remember API signatures, and manually implement patterns you’ve written a hundred times before.

The skill shifts from writing code to directing, reviewing, and architecting code. That’s not a downgrade. If anything, it’s harder. You need to understand systems at a deeper level to prompt effectively, review critically, and catch the subtle bugs. The people who think AI coding is “easy mode” haven’t done it seriously.

“We’ve Always Done It This Way”

“Humans are allergic to change. They love to say, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’ I try to fight that. That’s why I have a clock on my wall that runs counter-clockwise.” – Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, The OCLC Newsletter, No. 167 (March/April 1987)

I love this woman. Seriously.

The loudest critics of AI coding tools share one common trait: they haven’t seriously tried them. Not for a weekend side project. Not for a real production task. They tried ChatGPT once, got a wrong answer, and declared the whole thing a parlor trick. That’s like using a 1952 compiler once, getting a suboptimal binary, and declaring compilers a dead end.

The people who actually use these tools every day? They’re not the ones complaining. They’re too busy shipping software.

The “always done it this way” crowd in 1952 eventually retired. The compiler won. The “always done it this way” crowd in 2025 will eventually… well. You see where this is going. This isn’t about replacing skill. It’s about redirecting skill to higher-value work. The same thing compilers did. The same thing every abstraction layer has done.

What Grace Would Actually Say

So what would Grace say about all of this?

Look – she was a Navy officer, a mathematician, a pragmatist, and a radical. She didn’t care about the purity of hand-written code. She cared about getting things done. She cared about making computers accessible to more people, solving bigger problems, and not wasting human brainpower on tasks machines could handle.

I think she’d say something like: “You have a tool that lets you describe what you want in plain English and it writes the code for you? And you’re NOT using it? What is wrong with you?”

But she’d also say this: you still need to understand what you’re building. The compiler didn’t excuse you from understanding the problem domain. It freed you to focus on it. Same deal here. If you’re using an LLM coding agent without understanding architecture, without reviewing the output, without thinking critically about the design – you’re doing it wrong. The tool is a force multiplier. It multiplies whatever you bring to the table. Bring nothing, get nothing.

Grace Hopper would be first in line to use these tools. And she’d have zero patience for the naysayers.

The Pattern Never Changes

Every major abstraction in computing history was resisted by the people who had mastered the previous layer. Assembly programmers resisted compilers. C programmers resisted garbage collection. Desktop programmers resisted the web. On-prem folks resisted the cloud.

The pattern is always the same: the new abstraction wins because it lets more people build more things faster. Period. The people who adapt thrive. The people who cling to “we’ve always done it this way” become footnotes.

That’s not a threat. It’s an observation. And Grace Hopper made the same observation 70 years ago.

Conclusion

Grace Hopper fought this exact battle in 1952. She had working proof that a higher abstraction layer was not only possible but better, and the establishment refused to accept it. She won. The compiler won. And every programmer alive today benefits from her stubbornness.

The question isn’t whether natural-language-directed coding will become normal. It will. The question is whether you’ll be one of the people who embraces it, or one of the people who says “we’ve always done it this way.”

I know which side Grace would be on.

Get yourself a counter-clockwise clock.

Be like Grace!